New research dispels myth of conspiracy theorists as isolated outsiders

Posted on: 29 July 2025

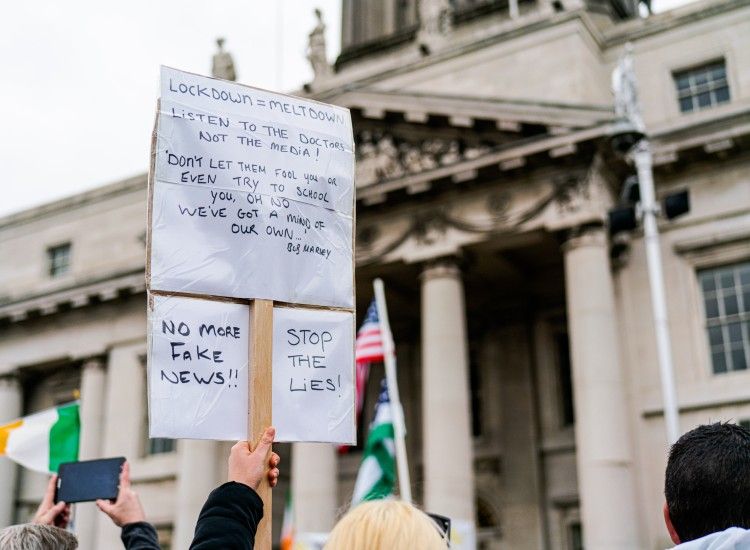

Dr Stephen Murphy, from Trinity Business School, said: “The uncertainty and fear caused by the pandemic created the initial spark for conspiracy beliefs to prosper. In both places, there was a lot of anger around lockdown restrictions, vaccinations and the way that authorities were handling the situation.”

Real-life study finds that the participatory culture offered by conspiracy theorists is expanding the scope of fringe ideas

A five-year study dispels the stereotype of conspiracy theorists as angry loners or keyboard warriors. Rather, social and emotional connections provided by conspiracy theorists are recruiting diverse participants on a growing scale.

The researchers, from the University of Bath’s School of Management and Trinity College Dublin, followed people on the cusp of becoming conspiracy theorists to understand how people become involved in fringe ideas. They joined closed groups in online social networks, and attended public meetings, conferences and protests.

“Although our research was conducted in the UK, we observed similar social dynamics at play in Ireland,” said co-author Dr Stephen Murphy, from Trinity Business School.

“The uncertainty and fear caused by the pandemic created the initial spark for conspiracy beliefs to prosper. In both places, there was a lot of anger around lockdown restrictions, vaccinations and the way that authorities were handling the situation. We wanted to understand the social dynamics at play as people searched for alternative explanations.”

“We were initially apprehensive about approaching groups often depicted as delusional, dangerous and angry,” said University of Bath's Dr Tim Hill. “In practice, when we went to events, we found people were welcoming, inquisitive, and enthusiastic. This social quality of these contexts became key to our findings.”

The researchers say they hope the study will reshape discussions of how people become involved in conspiracy theories, moving away from ideas that belief in conspiracy theory is motivated by personality or irrational thinking alone. By understanding troubling life circumstances and people’s subsequent search for solutions and support, this study helps to explain how and why conspiracy theories are growing.

The research, published in the journal Sociology, took place in two stages. During the first stage of data collection (2017-2018), they were introduced to a community interested in a variety of conspiracy theories. These included anti-5G narratives, flat-earth ideas, alternative health and vaccine hesitancy, as well as New Age spirituality.

During the second stage of data collection (2018-2022), the researchers attended various events organised by conspiracy theorists, attending public meetings, conferences and protests at locations in the South of England and South Wales.

From 32 interviews with 23 participants, they identified three main stages to believing in conspiracy theories. Firstly, an experience that leads people to question trusted sources of knowledge – in many cases this could be feeling let down by public sector services or authority figures, which leads them to feel emotionally connected to conspiracy ideas.

Secondly, people make sense of conspiracy theories together, which strengthens shared beliefs. Referred to as ‘awakenings’, people feel they are understanding the truth about the world for the first time.

Elle*, a 20-year-old massage therapist who came to believe that Covid-19 was coordinated by powerful groups of ‘deep state’ actors said: “My friends and I, we see the world now through a new set of eyes. The pandemic made us see the light, to see the truth. It was like a revelation.”

Dr Hill said: “Conspiracy theories provide reassuringly simple answers, but more than just solving problems, they create shared emotions, belonging and community.

“We went to venues that were buzzing - a campaigner opens with a story and then people stand up to share theirs. The campaigner will give their thoughts which are followed by clapping, giving a sense of solidarity and positivity that a clear, definitive answer has been identified.”

“People don’t necessarily join conspiracy communities sharing the exact same beliefs, but nevertheless the social connection is formed as people become immersed in doing their own research and sharing their findings with others,” said Dr Stephen Murphy.

In the final stage, people not only believe in the theories but also take action based on them - to protest as part of a conspiracy movement. Often this follows on from ‘doing their own research’ - reading official documents and taking on board a wealth of conspiracy-related information, which enables them to produce their own conspiratorial explanations.

Co-author Professor Robin Canniford, also from Bath’s School of Management, said: “The participatory aspect of conspiracy theories encourages people to become involved. It can feel very positive and supportive. It’s a thriving and welcoming social scene where people feel they are better informed about the workings of the world and are ready to take action.”

However, the social nature of conspiracy theory communities does not mean they are benevolent. One participant had become estranged from his family and received a criminal conviction following his involvement in anti-lockdown protests, demonstrating how conspiracy theories can tear apart families and lives.

Resonant Awakenings: the social lives of conspiracy theorists, is published in Sociology.

* Name changed to protect identity